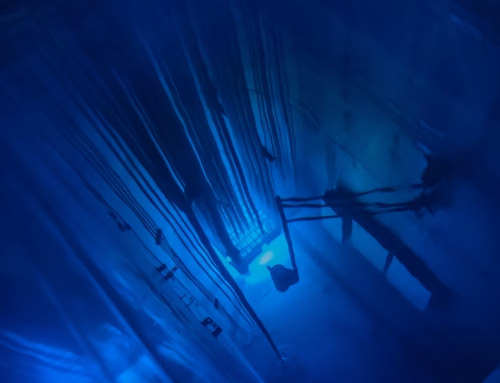

Project_1164_Moskva_2012_G2

Autor foto: Domena publiczna

Naval drones in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Implications for the Baltic Sea region

December 23, 2025

Author: Jakub Knopp

Project_1164_Moskva_2012_G2

Autor foto: Domena publiczna

Naval drones in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Implications for the Baltic Sea region

Author: Jakub Knopp

Published: December 23, 2025

Following the illegal occupation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, the Ukrainian navy, which had been underfunded and neglected for decades, found itself on the brink of collapse. Most Ukrainian ships lost their combat capability or were seized by the aggressors, with their crews surrendering as a result of the Russian operation. Another symbol of the deep crisis was the scuttling of the last frigate in service, which took place on the first day of the full-scale invasion in February 2022. Despite problems with financing, training, and the loss of key infrastructure in Crimea and the Sea of Azov, innovation, brilliant command, and skillful use of Western support meant that the Russian Black Sea Fleet not only failed to gain control of the sea lanes but was pushed to the eastern reaches of the Black Sea. This impressive achievement in the art of asymmetric warfare holds a number of lessons for NATO countries in the Baltic Sea region.

Click the link below to read the full Policy Paper.