PULASKI POLICY PAPER Wojna uderzyła w ukraiński system paliwowy Konieczna była całkowita reorganizacja systemu

Autor foto: Domena publiczna

Past, present and the future of the Ukrainian fuel sector. The origins of the fuel crisis and analysis of the viable support options during and post the Russian aggression

July 5, 2022

Author: Piotr Przybyło

PULASKI POLICY PAPER Wojna uderzyła w ukraiński system paliwowy Konieczna była całkowita reorganizacja systemu

Autor foto: Domena publiczna

Past, present and the future of the Ukrainian fuel sector. The origins of the fuel crisis and analysis of the viable support options during and post the Russian aggression

Author: Piotr Przybyło

Published: July 5, 2022

Pulaski Policy Paper no 11, 2022, 5th of July 2022

There are a few reasons for the current fuel crisis in the Ukraine, which reflects itself in the massive shortage of this good in the country. The country’s pre-aggression fuel demand (do not mistake with the Russian aggression of 2014) was mostly met by importation and only a minor share of fuel was produced nationally in Ukrainian refineries. It should be noted that the domestic fuel production was still vastly based on imported oil.

Fuel was imported from three main directions. Most of gasoline was transported from the south via Odessa – a main sea gate for the Ukrainian fuel import. This Black Sea passage is blocked now by the Russian military vessels. The other entry point for fuel imports (diesel in particular) was Belarus to the north. Similarly, Belarus ceased the import of fuel during the months preceding the onset of the current conflict. Imports from Lithuania were also affected as they were transported via territory of Belarus. Russia also supplied Ukraine with significant volumes of fuel which in the current military conflict situation between these countries has come to an end as this route is blocked. European Union countries predominantly from the west of Ukraine also provided fuel, but like the Ukraine domestic fuel production these volumes were never substantial. Additionally, the recent missile attacks on the remaining Ukrainian refineries and fuel storage facilities have resulted in internal production also needing to be replaced with imported fuel.

With the current Russian aggression and virtually total blockage of the original fuel supply routes and the destruction of domestic fuel production capabilities, there is a need to reroute Ukrainian fuel supply chains via alternative routes. The most obvious alternative appears to be the creation of new fuel supply chains from the European Union countries to the west of Ukraine: Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania. This however consequently creates a set of concerns and issues predominantly in the logistics and safety of the deliveries spheres since there is insufficient infrastructure and Ukraine is still heavily involved in the military conflict with Russia. Some of the potential viable solutions have already been implemented or will be implemented soon while others require more time and effort, substantial investment, and the construction of new infrastructure. At the time of writing, some solutions described have not been considered at all.

Ukrainian’s fuel sector pre-invasion

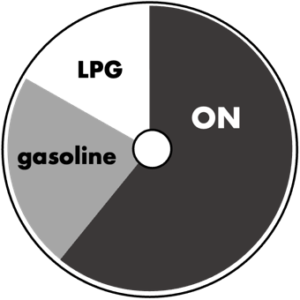

Ukraine is a country dependent on fuel imports. Ukraine’s domestic fuel market is relatively small, with the volume of automotive fuel sales slightly over 12 million tons (8 million tons ON, 2.2 million tons of gasoline, 2 million tons of LPG – see figure 1).

TOTAL DEMAND – 12 million tons of fuel

ON – 8 million tons – 66%

Gasoline – 2.2 million tons – 18 %

LPG – 2 million tons – 16%

Fig. 1. Ukraine, pre-war, yearly fuel demand with the division in fuel type

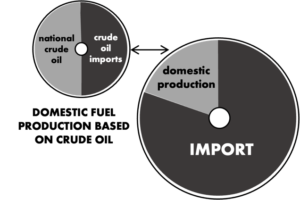

Ukraine, due to the outdated nature and lack of investments in the domestic refining industry, by February 24, 2022 (the first day of Russian aggression in 2022) was almost totally dependent on the import of automotive fuels and was unable to produce a large volume of Euro-5 fuels (European fuel standard) in domestic plants (figure 2).

TOTAL IMPORTS – 9,6 million ton of fuel – 80% (of 12 million tons)

ON – 6.8 million tons – 85% (of 8 million tons)

Gasoline – 1.2 million tons – 55% (of 2.2 million tons)

LPG – 1.6 million tons – 80% (of 2 million tons)

Remaining 2.4 million tons of fuel (20% of 12 million tons) comes from domestic production based on crude oil from which 50% (1.2 million tons) was imported via Black Sea

Fig. 2. Ukraine, pre-war, yearly fuel imports versus domestic production

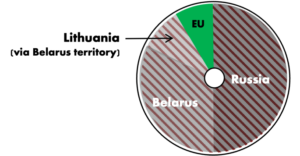

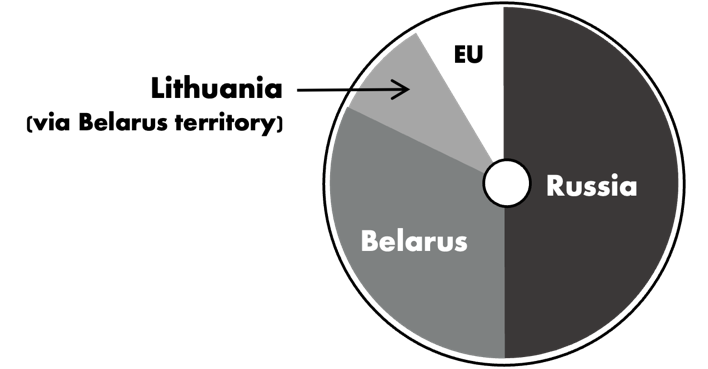

In 2021, Ukraine imported more than 85% of diesel, almost 80% of LPG, and almost 55% of gasoline. Importantly, most imports (80% of total imports) were made from Russia and Belarus, as well as through seaports (mainly via Odessa). Lithuania (refinery in Mazeikiu) also supplied Ukraine with almost 10% of their total imports (10% of total diesel imports – 690 thousands tons, and 11% of total gasoline imports – 265 thousands of tons) with this transit occurring via the territory of Belarus. Inland imports from other EU countries accounted for another 10% of the supplies (figure 3). Moreover, almost half of the domestic production of fuels (20% of total fuel supplies) was based on crude oil imported through sea oil ports on the Black Sea coast.

TOTAL – 9,6 million ton of fuel – 80% (of 12 million tons)

TOTAL – 9,6 million ton of fuel – 80% (of 12 million tons)

Russia + Belarus – 80% – circa 7.6 million tons of fuel

– Russia – 50% – circa 3.8 million tons of fuel

– Belarus 30% – circa 2.3 million tons of fuel

Lithuania – 10 % – circa 1 million tons of fuel

Other EU countries – 10% – circa 1 million tons of fuel

Remaining 2.4 million ton of fuel (20% of total 12 million tons) comes from domestic production based on crude oil from which 50% (1.2 million ton) imported via Black Sea

Fig. 3. Ukraine, pre-war, fuel import origins

Russia and Belarus cutting off Ukraine from fuel supplies

Just three weeks before the first day of invasion (do not mistake with the Russian invasion in 2014), Belarus introduced a ban on the rail transit of fuels from Lithuania, which seriously hindered the import of the Mazeikiu refinery’s production.

On February 24, 2022, the first day of the Russian invasion, the Ukrainians were further cut off from all the fuels imported from the Russian and Belarussian direction. About 70% of the LPG, almost 65% of the diesel and over 40% of gasoline needed were stopped from being transported to Ukraine. Moreover, the actions of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea cut off a further 5% of imported LPG and 15% of imported diesel.

Consequently, in a matter of days, Ukraine was deprived of fuel supplies totalling more than 70% of its total domestic consumption (more than 8.6 million tons / year, i.e. 0.72 million tons / month of fuels) and was forced to entirely reorganise the geography and logistics of deliveries of virtually all fuel types. Supplies from the Belarussian and Russian direction were later further reduced before being ceased completely resulting in almost 80% of the fuel supplies needed by Ukraine being unavailable (figure 4).

Remaining supply directions:

EU countries – 10% – circa 1 million tons of fuel

Fig. 4. Ukraine, war-time remaining fuel import origins

Destruction of the domestic refineries, fuel production, and storage infrastructure

The cessation of imports was not the only blow to the Ukrainian fuel market. From the first day of the aggression, Russian military forces targeted fuel production and storage facilities across the entire country. Shockingly, refineries, gasoline and diesel warehouses remain the most dangerous places for civilians and are continuously being targeted by Russian military forces.

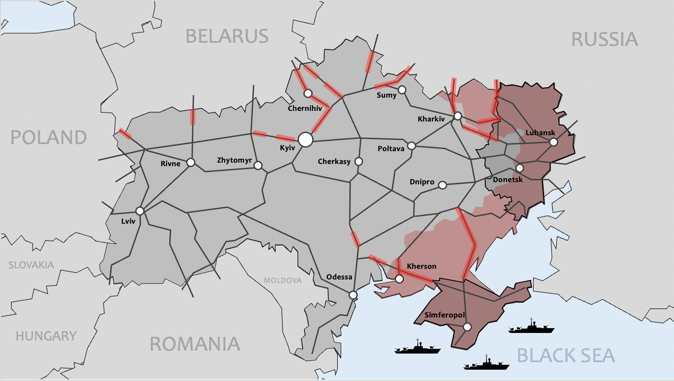

Pre-war, Ukraine had six refineries, with the potential to produce fuel products, however, the facilities were outdated. Fuel production was only carried out in the plant in Kremenchuk, in the central part of Ukraine in the Poltava Oblast, as well as a small plant in Shebelinka near Kharkiv (figure 5).

Fig. 5. Ukraine pre-war available fuel import directions. The map shows Ukraine’s pre-war available and used fuel import directions (marked by green arrows). Three separatists’ regions (Crimean, Donetsk and Luhansk regions) are also indicated. The map also shows Ukraine’s pre-war fuel production infrastructure with the six existing refineries. Please note that the fuel production was carried out only by the plant in Kremenchuk located in the central part of Ukraine in the Poltava Oblast, as well as a small plant in Shebelinka near Kharkiv. Four other rafineries (Odessa, Kherson, Nadvirna and Drohobych) remained without fuel production capabilities.

Kremenchuk technically was able to process 11 million tons of oil per year, but much smaller quantities were commercially viable. In recent years, it was only 2–2.5 million tonnes. Additionally, there were 13 other much small refineries operating in Ukraine with an oil processing and fuel production capabilities (e.g., Shebelynka in Kharkiv Oblast). These fuel production facilities could have satisfied up to 20% of the country’s demand – 2.4 million tons of fuel (producing only 50% of domestic needs of gasoline, 15% of domestic needs of ON and 20% of domestic needs of LPG). Unfortunately, in April 2022, Ukraine’s Kremenchuk oil refinery was destroyed after a Russian attack. The other remaining infrastructure was also destroyed throug the Russian aggression, so an urgent need for alternative foreign supplies became apparent (figure 6).

Fig. 6 Ukraine war-time available fuel imports directions. The map shows Ukraine’s war -time available fuel import directions (marked by green arrows). Different modes of fuel delivery exist in these directions (e.g. road tankers supplies, fuel pipeline transmission or Danube river transportation – see the main text for more information). The red arrows indicate pre-war fuel import directions, now ceased. The red area indicates the land currently occupied by Russian military forces. Three separatists’ regions (Crimean, Donetsk and Luhansk regions) are also indicated. The map also shows Ukraine’s fuel production infrastructure with the six refineries, from which four had been affected by the Russian military action. Please note that the fuel production was carried out only by the plant in Kremenchuk located in the central part of Ukraine in the Poltava Oblast, as well as a small plant in Shebelinka near Kharkiv. Four other rafineries (Odessa, Kherson, Nadvirna and Drohobych) remained without fuel production capabilities.

Although they had not been in operation for several years, the Russians also destroyed the refineries in Odessa and Lysychansk, most likely with the intention of preventing any future production of automotive fuels in Ukraine (figure 6). The only exception to the attack on Ukraine’s domestic fuel production is the LPG production scattered throughout the country. Although it has survived destruction so far, it has been at a lower level than before the pre-war period.

The fuel crisis has also been aggravated by attacks on critical infrastructure facilities related to fuel storage, which occasionally occurred in various districts. The Russians have systematically destroyed private and state fuel storage facilities, depriving Ukrainians of supplies and significantly impeding fuel logistics. The Ukrainians’ declarations show that 15 to 22 fuel bases were to be destroyed or significantly damaged. To date four fuel storage facilities in the cities of Mykolayiv, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia and Chuhuiv were destroyed and oil depots in Lutsk (Volyn region), Dubno (Rivne region), as well as in Lviv and Kryachky near Vasylkiv (Kyiv region) have sustained attacks.

Ukrainian fuel imports mainly through rail lines infrastructure

In the months leading up to the war, almost all fuel imports to Ukraine (over 80%) were carried out by rail lines, and less than 20% by sea and, to a very limited extent, by road tankers (figure 7).

9.6 million tons – 80% of fuel transported by rail

2.4 million tons – 20% of fuel transported by the sea

0.12 million tons – less than 1% of fuel transported by road tankers

Fig. 7. Pre-war transport modes of fuel import Ukraine. Pre-war transport of fuel into Ukraine was heavily dependent on rail infrastructure with 80% of fuel transported by trains. The remaining 20% of fuel transported entered the country by the sea (mainly via Odessa ports). Only small portion of the imports (less than 1 %) was transported by road tankers (mainly from the Western direction and EU countries).

Also, further distribution of fuels inside the country was largely realized thanks to extensive and relatively evenly covering the entire territory Ukrainian rail network (figure 8). The Ukrainian rail infrastructure contains of almost 20,000 km of rail lines, with nearly 9500 km of electrified track, over 85,000 freight wagons and nearly 2000 locomotives (1630 electric and 300 diesel locomotives). Only last year the rail cargo transportation exceeded 300 million tons. It is important to notice that the rail infrastructure in the western and south-western part of the country has not been greatly affected by the military actions, remains intact and can continue to be used for fuel distribution from the new directions (figure 8).

The Ukrainian railway network have a Russian gauge of 1.520mm, while in most of EU countries the tracks have an inner gauge of the rails at 1.435mm. In addition, the loading gauge offers more load in Ukraine than in the EU. These two technical imperatives have long limited trade between the Russian side for Baltic countries, Ukraine, and Belarus with the rest of Europe, especially on the Polish and Slovak borders. That is why, transporting any goods between countries with different rail gauge a long also requires the inefficient process of reloading the cargo at the border. For example, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus all have the same rail “broad gauge” allowing fuel supplies to be transported from Lithuania to Ukraine (via Belarus) along the same gauge for the entire distance. These supplies must now make a detour via Poland as Belarus territory cannot be used due to military hostility. Reloading at fuel terminals on the borders of Lithuania and Poland, as well as Poland and Ukraine now make the entire process approximately twice as long and costly.

Fig. 8. The Ukrainian pre-war extensive railway network and the war-time destruction of the infrastructure. The figure shows two maps – pre-war rail line infrastructure. The figure shows two maps – pre-war rail line infrastructure and war-time destruction located mainly in the northern and eastern part of the territory. The red lines indicate destroyed rail line sections (the map of the right). Please note that the rail infrastructure in the western and south-western part of the country is intact and can continuously be used for fuel distribution from the new directions. The red area (the map on the right) indicates the land currently occupied by Russian military forces. Three separatists’ regions (Crimean, Donetsk and Luhansk regions) are also indicated.

Although Ukraine announced publicly that will construct railway tracks of European standard in the future, it is worth adding, however, that the modification of the tracks from the current 1520 mm to the standard 1435 mm is almost impossible to implement during the war. This investment would be also very costly and requires a temporary suspension of freight services on the modernized routes. Additionally, it requires the reconstruction of hundreds of railway stations across the country.

Due to the changed gauge of rails on the border of Ukraine and EU countries, as well as the lack of tradition of larger fuel supplies directly from the EU, no significant infrastructure for fuel transhipment has been built on the western borders of this country. An exception, and of little importance given the current scale of Ukraine’s needs, is ORLEN’s rail transhipment terminal in Zurawica near Przemysl in Poland.

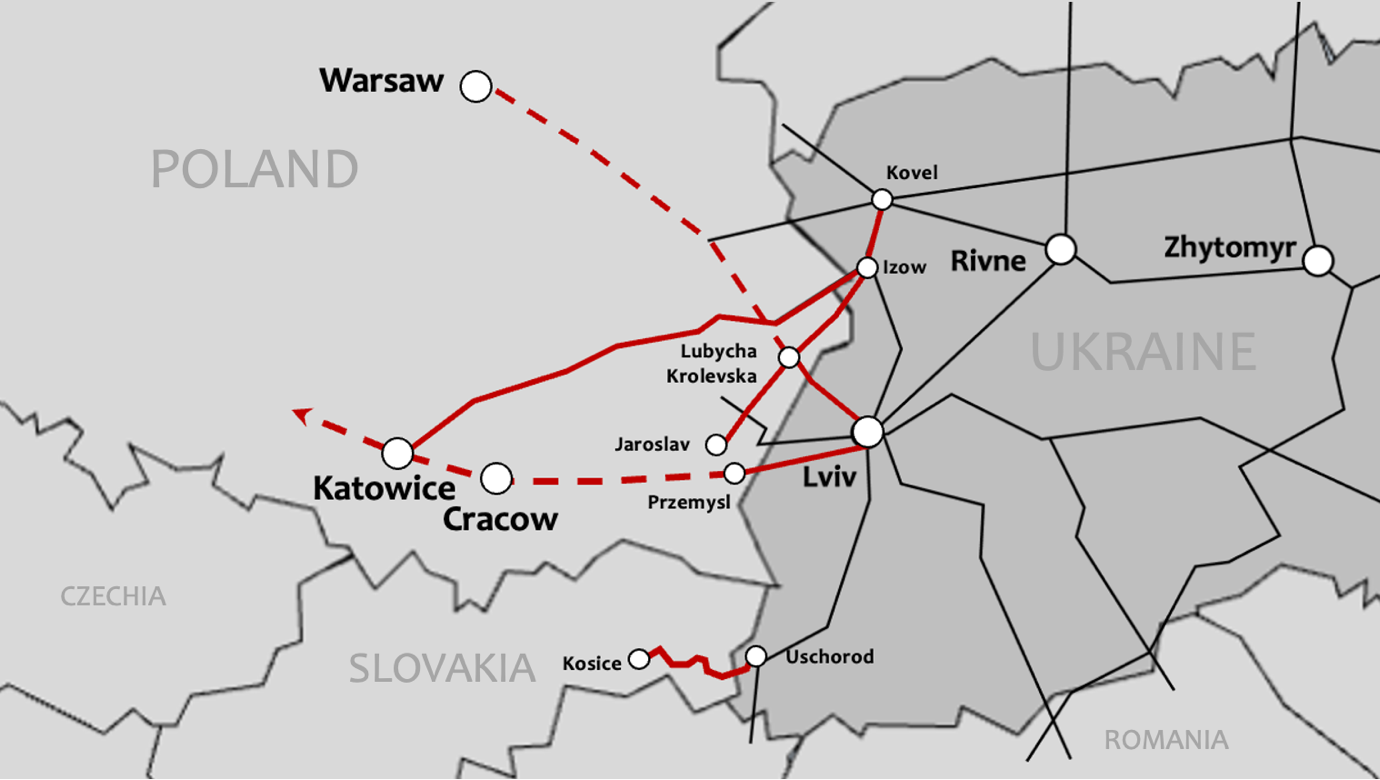

Fig. 9. Existing rail infrastructure where two different rail gauge systems overlap. The map shows the most viable rail connections between Ukraine and EU countries where European – gauge system exists on the territory of Ukraine and where the broad – gauge system used in Ukraine exists in EU countries (predominantly in Poland). The rail lines marked in red allows the transport between Ukraine and EU countries without reloading process at the border. For a detailed description see the appendix.

The map depicts rail line routes:

Broad-gauge in EU countries:

1. LHS line

2. Ushhorod–Kosice track

EU gauge in Ukraine:

1. Lviv – Medyka future dual gauge railway route (planned)

2. Lviv-Rava-Ruska-Warsaw future dual gauge railway route (planned)

3. Jaroslav – Kovel line

The only feasible immediate option would be to use an existing rail infrastructure where two different rail gauge systems overlap (figure 9, see also appendix for a detailed description). The broad-gauge routes in EU countries as well as EU gauge routes in Ukraine could be used for transhipment of fuel without the need of reloading at the border between Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine, however no significant fuel production or fuel storage facilities (refineries, fuel depots etc.) exists nearby, and such infrastructure would need to be constructed to adapt the lines to the fuel transportation needs on both sides of the border. Some analysis of viability of usage by modern railway cistern systems would also need to be conducted.

Ad-hoc solutions

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion and gradual deterioration of the ability to import fuel from the original direction (Russia and Belarus) and/or produce it domestically, certain measures were implemented to increase the daily volume of fuel imports from the EU from 4,000 tons to 12,000 tons per day (up to 360,000 tons of fuel per month – see figure 10).

These measures included:

- Revoking permits for entry of tank trucks for fuel delivery to Ukraine;

- opportunity to receive fuel in the ports of the Danube;

- changes to the mechanism of price regulation of fuel prices;

- extraordinary registration of fuel at the borders by the customs and border services.

As a result, the railway began to import 5 times more fuel to Ukraine and just in May 2022, 180 thousand tons of fuel were delivered. Its deliveries, instead of going by the shortest and simplest logistically route from Lithuania via Belarus to Ukraine (all these countries have the same rail gauge – “broad gauge”), had to make a detour through Poland, with reloading at fuel terminals on the borders of Lithuania and Poland, as well as Poland and Ukraine.

Road tankers deliveries increased 15 times – from 5,000 to 85,000 tons of fuel. River transport (via Danube River) now transports 5 times more fuel than in March – from 4,000 to 22,000 tons of fuel (monthly).

TOTAL IMPORT from new logistic routes – 360,000 tons – 100%

180 thousand tons – 50% – rail lines

85 thousand tons – 25 % – road tankers

50 thousand tons – 13% – fuel pipeline

25 thousand tons – 7% – confiscated Russian and Belarussian fuel halted on the territory of Ukraine

20 thousand tons – 5% – river transport

Fig. 10. War-time total transport of fuel into Ukraine – new logistics routes with the new measures implemented.

There is also an agreement to start reversing fuel by existing pipe transport from Hungary. Ukraine has received confirmation of imports of 35,000 tons per month, with a potential increase to 50 thousand tons. Meanwhile, customs launched a separate green lane for fuel trucks from Poland, potentially increasing the throughput from 110 to 200 units (road tankers / cisterns) per day.

There is a further plan of action for the coming weeks and months to stabilise the volumes of supplies long term:

- to obtain the consent of the EU countries for the guaranteed acceptance of fuel tankers for the Ukrainian market by their ports;

- to confiscate Russian and Belarusian fuel that was imported before the Russian invasion and is now under arrest;

- load diesel pipeline from Hungary;

- to make systematic purchases by the national operator NJSC Naftogaz of Ukraine to have rhythmic deliveries and long-term contracts.

All the mentioned initiative are being implemented to overcome the current fuel crisis and stabilise the prices in Ukraine for public and military use. With that in place, Ukraine is receiving approximately 360,000 tons of fuel from completely new logistics routes. However, although the ad-hoc measures with the volume of 360,000 tons of fuel will allow Ukraine to overcome the domestic crisis and continue the military operations for the time being, there are by no means sufficient to support a large military counteroffensive, continue rebuilding destroyed infrastructure, cities, and countryside and allow pre-war fuel consumption in the country. Therefore, a robust plan to supply pre-war fuel volumes (approx. total 12 million tons of fuel) must be drafted and implemented.

Long term solutions

Establishing a stable, effective, and efficient fuel window to the world for Ukraine is a task for years. At present, it is unknown for sure what the frontline will look like at the time of a future ceasefire or the eventual end of the war, so it is not known what the future challenges and opportunities for Ukraine to import fuels and crude oil will look like. The pessimistic scenario assumes that Ukraine may be cut off from sea oil and oil ports for decades and, consequently, the only direction from which imports will be possible will be its borders with the EU. According to the optimistic scenario, some or all Ukrainian ports will function, hence the import of fuels and possibly crude oil will also be possible from the sea. The most difficult thing to imagine is the possibility of returning to business as usual and importing oil production from Russia and Belarus as status quo ante. Such a scenario would probably only be acceptable if a pro-Western shift took place in both countries. Even with the implementation of the most optimistic scenario in the coming years Poland will remain a logistics hub for fuel supplies to Ukraine, with a much larger share than Romania, Slovakia, or Hungary.

Conclusions for Ukraine and for Poland

1. Due to the closure of the fuel supplies from Russia and Belarus, the blocking of seaports and the destruction of the Ukrainian refineries, Ukraine has been forced to rapidly change the supply routes of the domestic fuel market and the logistics of deliveries. The only feasible direction of the fuel supplies remains EU countries (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania – see figure 6). The western part of Ukraine is also relatively less affected by the military conflict, the overall road and rail lines infrastructure least destroyed and relatively safer for conducting reliable fuel transportation. With forecasts of the Ukrainian market demand to meet in June this year 0.13 million tonnes of gasoline will be required (66% of the average monthly demand of the Ukrainian market before the war) and 0.26 million tonnes of diesel (40% of the average monthly demand of the Ukrainian market before the war). There are currently no forecasts for the LPG market. Such numbers can be met via EU direction routes since the supply sources are not only the nearest refineries of ORLEN and LOTOS (Poland, Czech Republic, Lithuania), MOL (Slovakia, Hungary) and plants in Romania, but also the high liquidity markets of Western countries, in particular Germany.

2. The future of fuel supplies to Ukraine will not be able to resemble the current situation forced by the war, where significant portion of them is delivered to Ukraine by car tankers via Poland and then distributed directly to petrol stations in that country, bypassing fuel bases. Such logistics, although mitigating the current crisis, are inefficient and not profitable due to the relatively high costs of truck freight. Their role on the border of Poland and other EU countries with Ukraine should be taken over by rail supplies, which means the need to build new fuel terminals. These can be located on the borders of Ukraine, like the already operating Zurawica fuel terminal, or in the interior of Poland on the Broad-Gauge Metallurgical Line or similar rail lines (figure 9). It is possible that the change in the general directions of fuel import / export from and to Ukraine will also force Ukraine, Poland, and other EU neighbouring countries to invest in the development of the additional railway infrastructure. Viable alternative to rail deliveries are transmissions via fuel pipelines, however, the Hungary seem to have preferences here, as they are already connected to Ukraine by fuel pipeline with a capacity of 3.5 million tons yearly. Construction of fuel pipeline between Poland and Ukraine alongside gas and oil pipelines is also an option. Institutions such as the World Bank, American DFC or EU funds can determine whether new fuel infrastructure can gain financial support. President Biden also wants to facilitate support for investments that will reduce the effects of the war also outside Ukraine. This creates opportunities for investments also in Poland. The authorities of Poland and other EU countries should conduct business analyses of both above-mentioned investment options (construction of rail lines and pipelines). One fact however remains clear – the Polish border with Ukraine has become, unexpectedly, both for Poland and Ukraine, the gateway and the main source of fuel supplies to this country.

3. The destruction of the Ukrainian fuel storage infrastructure means that investments in this direction will also be necessary, not only in Ukraine but also in neighbouring countries. Historically, Ukrainians admitted that a part of the strategic reserves of Ukrainian fuels could be located outside of the country borders, for example in Poland. Also in this case, the storage needs necessary infrastructure for the effective implementation of fuel supplies to Ukraine and its protection in the event of subsequent crises should already be analysed.

4. Ukraine also signals an intention to rebuild the production capacity of domestic refineries so that the country can independently secure their production in the future. The construction of a new refinery in Ukraine, although it cannot be ruled out, is not necessary to guarantee its security in the fuel market. The likelihood of construction is reduced by its enormous costs and the long duration of possible investment, low domestic oil production, the risk of destroying the refinery during the current or future war, and the declining nature of the automotive fuel market. This may also be supported by financial resources that Ukraine may receive for its reconstruction after the war from the EU and USA. Consequently, it is possible that Polish companies could also participate in its construction / operation of these facilities. However unlikely at the current stage, Odessa-Brody-Plock oil pipeline, planned in the recent past by both Poland and Ukraine, could be part of this investment.

5. An important lesson for Poland, brought by the war in Ukraine, is the issue of securing supplies and production of fuels in the country in a situation of a possible war with Russia. De-russification of the Polish fuel market means a higher dependency on LNG ports in Swinoujscie and in Gdansk (in the future) and any failure or sabotage will generate significant problems and a threat to the Polish energy security. Destruction of fuel bases because of an attack should be considered as one of the scenarios and appropriate mitigation measures should be analysed and prepared, e.g., by expanding the infrastructure and further sources diversification.

Author: Piotr Przybyło, Research Fellow of the Economy and Energy Programme at the Casimir Pulaski Foundation

The Paper was prepared in cooperation with International Centre for Ukrainian Victory

APPENDIX

Fig. 9. Existing rail infrastructure which allows to connect two different gauge systems (broad – gauge and European gauge) between Ukraine and EU countries.

The map shows the most viable rail connections between Ukraine and EU countries where European – gauge system exists on the territory of Ukraine and broad – gauge system used in Ukraine exists in EU countries (predominantly in Poland). The map depicts connections:

Broad-gauge in EU countries:

- LHS line

- Ushhorod–Kosice track

EU gauge in Ukraine:

- Lviv – Medyka future dual gauge railway route

- Lviv-Rava-Ruska-Warsaw future dual gauge railway route

- Jaroslav – Kovel line

Feasible immediate option of using an existing rail infrastructure where two different rail gauge systems overlap. Below the most viable options are presented.

Broad-gauge in EU countries

a) Broad-gauge in Poland – LHS line

The LHS line (the so-called “wide track”) is the longest broad-gauge railway line in Poland (with a rail gauge of 1520 mm) intended for freight transport. It is also the westernmost broad-gauge line in Europe constructed in 1970 by Russians to gain the access to Silesian coal mines at the time of the Soviet bloc. It connects the Polish-Ukrainian railway border crossing Hrubieszow / Izow with Silesia, where it ends in Slawkow in Zaglebie Dabrowskie (25 km from Katowice). It is almost 400 km long (the exact length of the line is 394,650 km). The LHS line has a specific regional range (it runs through south-eastern Poland). The attributes of the LHS line are transport without the need to reload goods at the border and the possibility of running heavy whole-train depots.

Although it is mainly a single track with few stations, the freight traffic in the direction of Ukraine still concerns around 10 million tons/year (data from 2016), which needs 6 to 8 trains per day. Ukraine is therefore still well connected to Europe.

b) Broad-gauge in Slovakia – Ushhorod–Kosice track

The Ushhorod–Kosice broad-gauge line is a single-track 1,520-mm-gauge railway mostly in eastern Slovakia, which currently is used especially for transporting iron ore from Ukraine to the steel works near Kosice. The length of the line is 88 km (with 8 km in Ukraine).

In 1978 it was decided to build a Russian gauge line in former Czechoslovakia to improve the imports of iron ore from Soviet Union to Slovakian steel works in Kosice. Construction started on 4 November 1965, and the line opened on 1 May 1966. It was electrified in 1978. Due to a rail line section between Trebisov and Ruskov where the gradient is over 15 ‰ two electric twin-unit locomotives are needed. The line transports approximately 8-10 million tons/year (data from 2018) with the trains reaching cargo loads of 4800 tons each.

European gauge in Ukraine

c) Lviv – Medyka future dual gauge railway route

Ukrainian Railway (UZ) also intends to construct a dual gauge railway to the border with Poland. The dual gauge railway is a design of four tracks, combining the European gauge and broad-gauge track sizes. It will allow the company to launch the direct trains from Ukraine to the European Union without bogie exchange.

The 70-kilometre route from Lviv in Ukraine to the border with Poland in Medyka is planned to be converted from the conventional broad-gauge railway of 1,520 millimetres to the dual gauge line by adding the parallel tracks for 1,435-millimetre gauge.

d) Lviv-Rava-Ruska-Warsaw future dual gauge railway route

Ukraine also announced the construction of a new line that will connect Lviv with Warsaw directly. The distance from Warsaw to Lviv is approximately 330 km. Today, European tracks run from Poland 7 km deep into the territory of Ukraine – to Rava Ruska. There are 58 km left to construct from Rava Ruska to Lviv.

Only on the Lviv Railway (Lviv railway district), as a remnant of the Polish rail line construction pre-Second World War, the total length of dual gauge (1520 and 1435 mm) is about 150 km dispersed along the border with Poland and elsewhere.

e) Jaroslav – Kovel line

The Jaroslav – Kovel line is a branch line in Poland and Ukraine. It runs from Jaroslav, a small town in eastern Poland, to Kovel, a railway junction in western Ukraine. The line, with a gauge of 1435 mm (European standard gauge; in Poland to Werchrata) or 1520 mm (Russian broad gauge; from Werchrata), is single-track and not electrified. Operations are run on the Polish section by the Polish State Railways, on the Ukrainian section by the Ukrainian Railways. Last year, 300,000 tons of goods were reloaded at the station in Werchrata, with some potential to expand the transhipment capacity in the future.

All the mentioned above rail lines could be used for transhipment of fuel without the need of reloading at the border between Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine, however no significant fuel production or fuel storage facilities (refineries, fuel depots etc.) exists nearby, and such infrastructure would need to be constructed to adapt the lines to the fuel transportation needs on both sides of the border. Some analysis of viability of usage by modern railway cistern systems would also need to be conducted.