przybylo-energy-1 copy

Autor foto: Domena publiczna

Europe’s Double Standards In Securing LNG Shipments. Can LNG Replace Russian Gas as a Source of Energy for Europe?

15 lutego, 2023

przybylo-energy-1 copy

Autor foto: Domena publiczna

Europe’s Double Standards In Securing LNG Shipments. Can LNG Replace Russian Gas as a Source of Energy for Europe?

Autor: Piotr Przybyło

Opublikowano: 15 lutego, 2023

Pulaski Policy Paper no 6, February 08, 2023

Natural gas is the cleanest fossil fuel; its CO2 emissions are about half of that of coal and just one-third of brown coal emissions. Replacing coal with gas reduces total emissions by hundreds of millions of tonnes annually in Europe. Consequently, natural gas is widely used for heating, cooling, electricity generation, creating indispensable materials (such as steel and concrete), and more. This source of energy currently represents around a quarter of the EU’s overall energy consumption. About 26% of that gas is used in the power generation sector (including in combined heat and power plants), and around 23% in industry. The remaining 51% is used in the residential and services sectors, mainly for heat generation in buildings.

The EU’s gas demand is around 400 bcm (billion cubic meters) yearly, and the entire continent (including the UK, Ukraine, and other non-EU members) requires a minimum of 550 bcm (data for the 2021 year). As domestic gas production is declining, and due to the current energy crisis, Europe is making effort to diversify its gas supply, reduce consumption across all sectors, accelerate the energy transition and implement carbon emission initiatives. All at the same time.

One might think that each step to phase out Russian fossil fuels brings the continent closer to a more secure and sustainable energy supply, in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal and the EU’s 2030 energy and climate targets. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth. Russian gas continues to flow to Europe in the form of LNG (liquified natural gas) and Europe is funding the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

LNG, proposed as an alternative to the Russian gas transfer, reveals that Europe can afford only an ad-hoc established energy security strategy and a reactive rather than proactive approach. EU actions also clearly expose a fickle manner in dealing with previously established objectives of the climate change policies, and double standards when dealing with energy solidarity across the continent. The current actions are pushing the entire continent towards the possibly of a similar energy crisis in the future. Until Europe develops its own energy source (regardless of its type) and establishes a clear and long-lasting energy strategy, the continent will be subjected to dependency on external LNG providers with unexpected shortages, the possibility of supply chain cuts, or shifting political sides of the gas-producing states. In the unstable global situation and at the brink of decoupling of global energy supply chains and ongoing conflict in Ukraine, this doesn’t seem to be a wise approach.

Europe Entangled by Russia’s Gas Tentacles

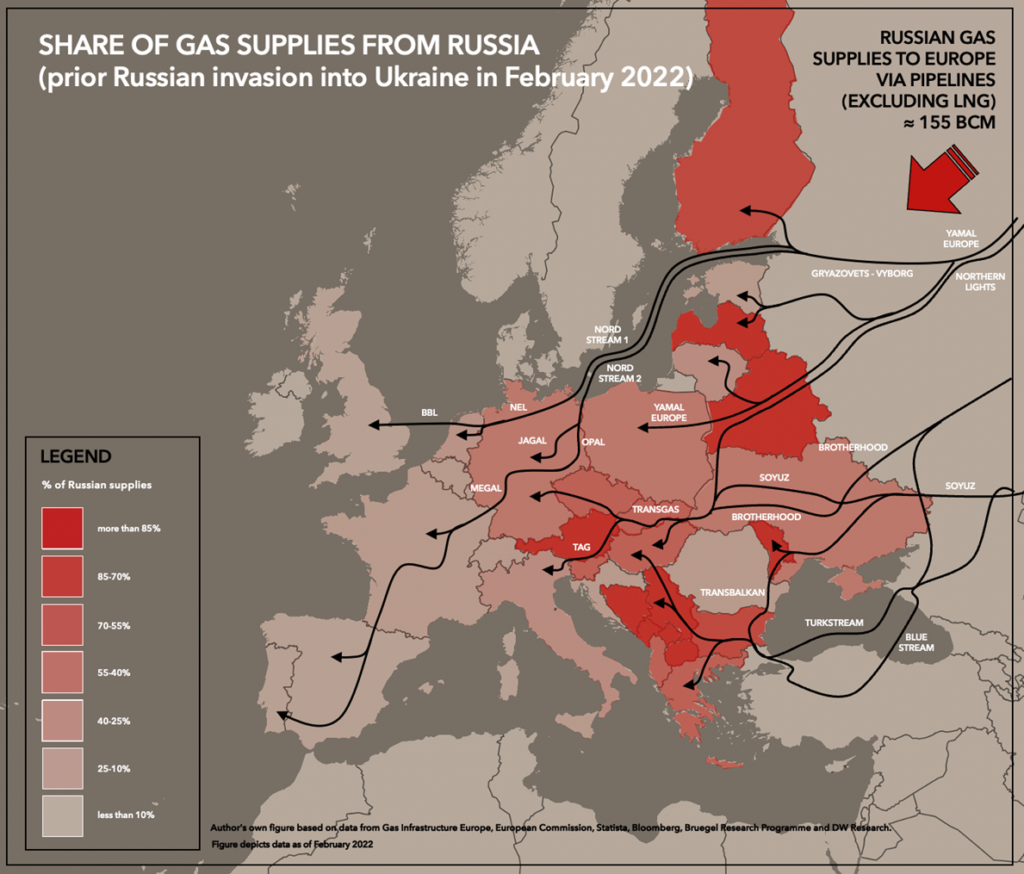

Around 10% of the European gas needs are currently met by domestic production. The rest is imported by pipelines or via LNG terminals. Pipeline gas imports have been dominated by Russia in the past years. In 2021, the European Union imported 155 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia, accounting for around 45% of EU gas imports and close to 40% of its total gas consumption. Progress towards Europe’s net zero ambitions assumed long-lasting gas supplies from Russia to be used as transition fuel towards net zero targets to combat climate change.

Following the military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Russian pipeline gas imports has fallen dramatically to approximately 500 mcm (million cubic meters) per week. Russia has been delivering natural gas to Europe via five main routes, three of them still transporting gas to Europe (figure 1).

With a capacity of 55 bcm yearly Nord Stream 1 was a route bypassing the Eastern European countries and delivering the gas directly to Germany, the Netherlands, and France. On certain occasions, Russian gas was delivered as far as the United Kingdom, Spain, and Portugal (figure 1). Last year, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia started reducing gas supplies through Nord Stream 1 for several months until late August, when Nord Stream 1 was shut down entirely.

Nord Stream 2, a twin pipeline, never delivered any gas. The certification process of the twin pipeline was suspended In September 2022 once Russia’s fateful decision to formally recognise two pro-Russian, breakaway regions in eastern Ukraine. Nord Stream 1 and 2 routes are closed since last year’s sabotage, during which, the explosions left 3 out of 4 lines damaged. As investigators piece together clues, Russia has quietly taken steps to begin expensive repairs on the giant gas pipeline.

Yamal-Europe pipeline (with a capacity of 33 bcm) delivered gas through Belarus and Poland to Germany and further to the West (figure 1). In May 2022, Russia’s Gazprom stopped the transit of natural gas via the section of its Yamal-Europe pipeline. Since then, the route (at a time responsible for nearly 15% of gas supplies to Western Europe and Turkey) has ceased.

A route through Ukraine, via a complex system of gas pipelines, delivers gas to Slovakia and further distributes it to Czechia and Germany, Austria, and Italy as well as via Hungary further to Serbia (figure 1). Even though Ukraine is partially occupied by Russian military forces and the country doesn’t receive any transit fees from Russia, some gas still flows through Ukrainian territory, although at their historically lowest levels of approximately 150-200 mcm.

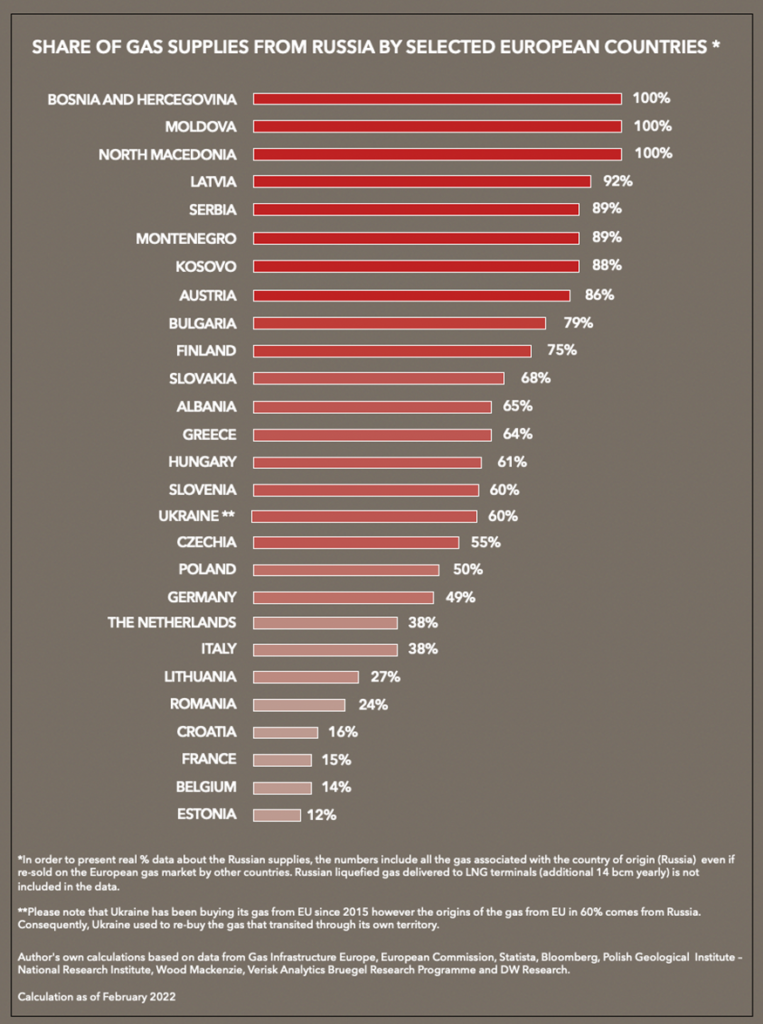

FIGURE 1. Share of gas supplies from Russia across European countries. In order to present real % data about the Russian supplies, the numbers include all the gas associated with the country of origin (Russia) even if re-sold on the European gas market by other countries. Russian liquefied gas delivered to LNG terminals (additional 14 bcm yearly) is not included in the data. Figure depicts data as of February 2022.

TABLE 1. Share of gas supplies from Russia by selected European countries. Please note that Ukraine has been buying its gas from EU since 2015 however the origins of the gas from EU in 60% comes from Russia. Consequently, Ukraine used to re-buy the gas that transited through its own territory. Presented calculations as of February 2022.

The fourth route via the Black Sea was opened in January 2020. Turkstream which transports gas to Turkey and further to Bulgaria, Greece, and North Macedonia is operating at approximately 200 mcm (million cubic meters) / daily (figure 1). This route was also used to transport gas via Serbia to Hungary, Austria, and Romania. Via Serbia, the gas was also transported to Bosnia and Hercegovina.

The fifth route is LNG deliveries from Russian LNG terminals on the Yamal peninsula which continue transporting Russian gas to Europe at an increased level (figure 2).

Europe Continues to Import Large Amounts of Russian Gas Despite Sanctions

Despite significantly reducing the import of pipeline natural gas and oil, the EU continues to import large amounts of Russian liquid natural gas (LNG) remaining a key importer of Russian LNG. Surprisingly, the import of Russian LNG has increased by approximately 15% since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine (as of January 2023).

In 2022, EU countries imported 16.5 bcm of Russian LNG. Unlike pipeline oil, there has not been and currently is no European embargo on deliveries of Russian LNG.

Consequently, the Russian LNG import to France has increased substantially. Spain, the Netherlands, and Belgium have also increased the amount of LNG received from Russia. Russian ships loaded with LNG from the Yamal peninsula continue arriving at the European terminal where LNG is converted to gas, fed into the European gas transmission system, and further distributed.

France is commonly held up as being less dependent on Russian natural gas than its neighbours like Germany, in central and eastern Europe – partly due to its reliance on electricity generation from nuclear power plants. However, this assessment ignores France’s growing imports of LNG. Some of these imports of Russian LNG in fact pass onward to Germany in the form of pipeline gas. Last year France announced that it would begin supplying limited quantities of natural gas to Germany under agreements for European solidarity. No one would, however, imagine that solidarity with countries that suffer gas deficit means using the gas from a country that created this crisis.

Thus, while countries like Germany receive less Russian gas via pipeline, some of the resulting shortfalls are made up by other countries, namely France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Spain with Russian gas they import in the form of LNG. Arguably, the financial benefits of individual EU members and their individual energy security appear to be more important than a joint European Union energy security. An EU energy security strategy cannot be achieved in a situation when certain EU states put their own interests above energy solidarity and combined energy security.

Lack of Sufficient LNG Volumes On World Markets

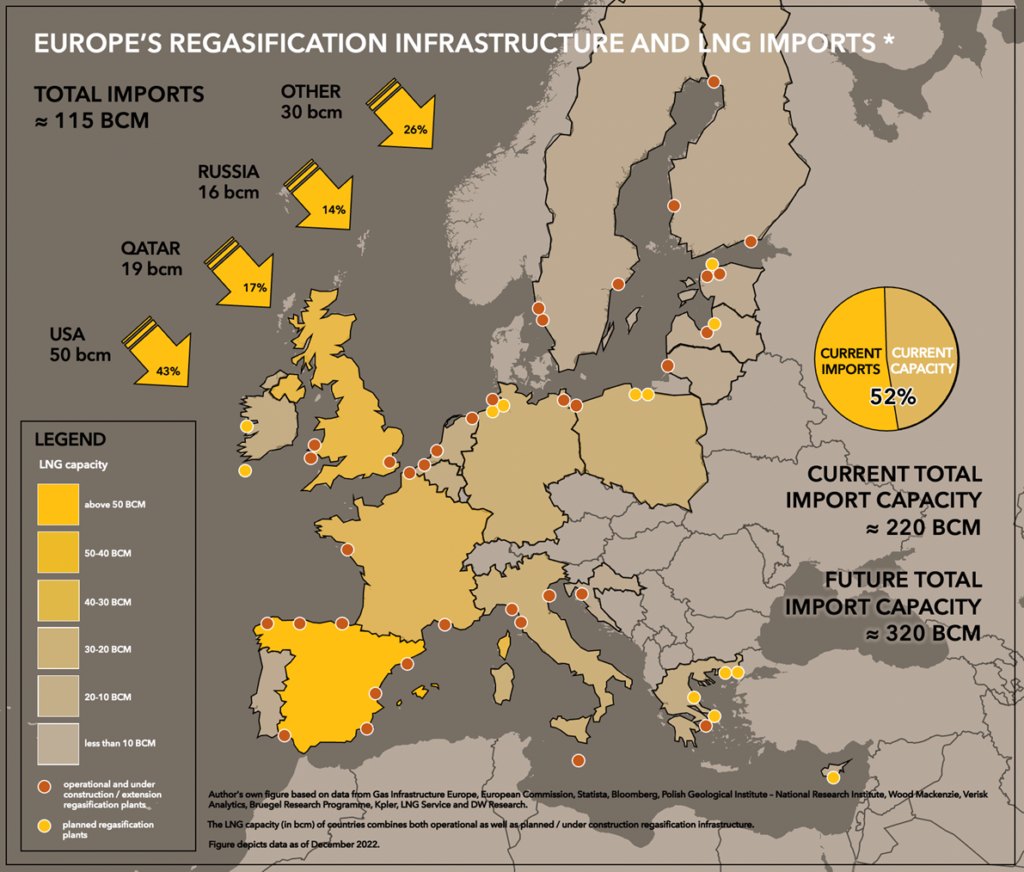

Importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) is another way Europe is planning to diversify the suppliers and routes used for Europe to obtain natural gas. Europe is already the largest LNG importer in the world. In 2022, Europe imported over 115 billion cubic meters (bcm) of LNG. France was the largest LNG importer, ahead of Spain and Belgium.

Last year, the United States was the largest LNG supplier to the EU, representing approximately 50% of total imports. Year on year, LNG imports from the US more than doubled. This number was followed by imports from Qatar and Russia (figure 2). Other LNG imports include transports from countries like Algeria, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, Australia, and others.

Europe’s overall LNG import capacity is significant (around 220 bcm in re-gasified form per year) – enough to meet around 45% of total gas demand. However, access to LNG infrastructure is uneven across the EU although Eastern European plans of expansion cannot be ignored, particularly in Poland (figure 2). Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and weaponization of gas supplies pushed European states to further develop their LNG infrastructure. Several planned investments are to be treated as EU projects of common interest, which benefit from streamlined procedures and, in some cases, co-financing.

This however doesn’t resolve the gas shortage in the European markets since the current European capacity for regasification was utilised at a mere 52% (figure 2). European countries struggle to import enough LNG which can then be effectively distributed across the continent. A lack of sufficient transit capacity in the current gas pipeline infrastructure, and snail-pace development of interconnectors between countries are some of the issues to be solved.

Yet the main obstacle is no spare LNG volume in the world market. Europe’s sudden shift into an LNG market cannot accommodate its immediate need for such immense volumes. The lack of Europe’s long-term strategy and stable investment required in the production of fossil fuel is the main reason for it.

FIGURE 2. Europe’s regasification infrastructure and LNG imports. The LNG capacity (in bcm) of countries combines both operational as well as planned / under construction regasification infrastructure. Figure depicts data as of December 2022.

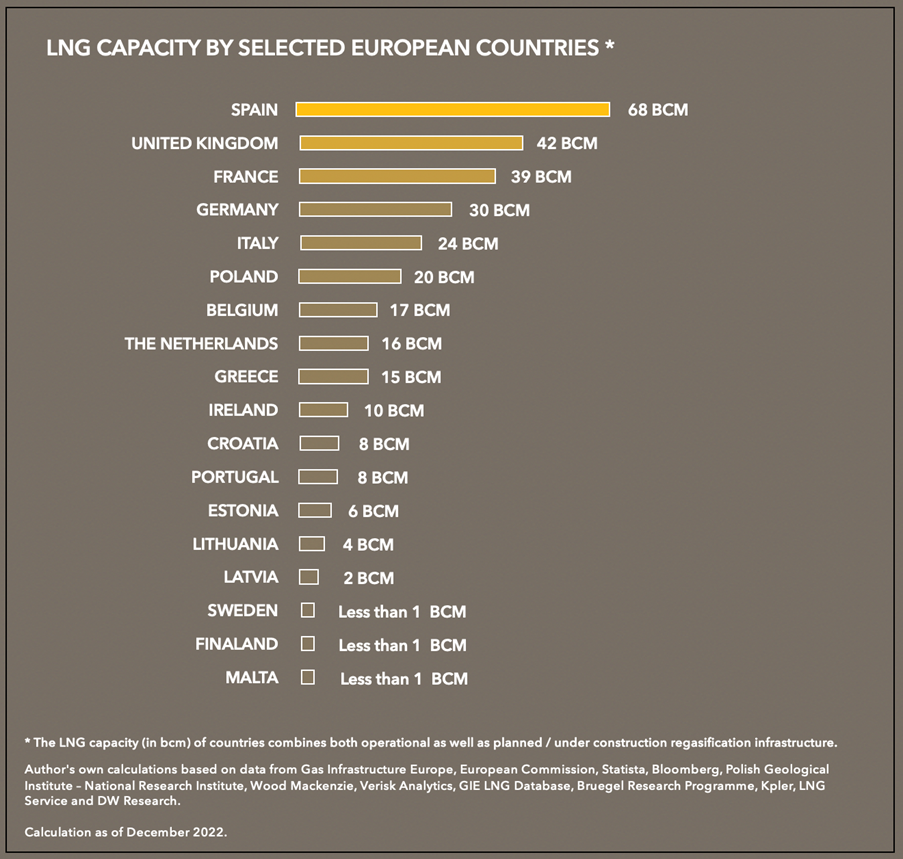

TABLE 2. LNG capacity by selected European countries. The LNG capacity (in bcm) of countries combines both operational as well as planned / under construction regasification infrastructure. Presented calculations as of February 2022.

Shortage of LNG Shipping Capacity and Limited FSRU Fleet

Even with enough LNG volume available on the market, Europe might face an infrastructural obstacle. After the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, several European countries have announced plans for the construction of new LNG terminals to reduce dependence on Russian gas imports.

Most of the plans are for floating LNG import facilities – known as FSRUs (floating storage and regasification units) – which can be installed more quickly than onshore, permanent import terminals. Currently, nine European countries are planning to operate new FSRUs within the next three years. Because of high demand and with the current global fleet limited to only 45 units, leasing rates for FSRUs have increased by 50% or more since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Competition between European countries to secure lease contracts became inevitable and will benefit countries willing to secure longer-term contracts and to accept higher rates.

Some LNG producers, who are ramping up exports to meet the European demand, have been caught out by constraints on ship supply. With 640 LNG ships globally, the world will lack the LNG shipping capacity to meet transport demand by 2025, or possibly before.

Until a common energy strategy to overcome the current energy crisis is forged, European countries will compete on the LNG shipment and FSRU market. This doesn’t boost cooperation and stands against the energy solidarity mechanism on the continent. Whilst Germany managed to secure its first two FSRU contracts in such a short period of time mainly because of its higher fiscal flexibility, other countries might struggle to accept such a high price.

Europe’s Preference of LNG Spot Market Adds to the Energy Crisis

The current crisis has also revealed much about the LNG market. The paradox of the situation lies in the fact that Europe’s natural gas crisis is, to a large extent, the result of attempts in recent decades to deregulate the markets and increase the role of spot trading.

In recent years, LNG investment decisions have been made in the absence of long-term contracts that would guarantee utilisation. Risks that may be acceptable for some commercial companies, however, are not always acceptable for governments of the countries that are the main LNG exporters.

While many independent LNG developers rely on long-term contracts to underpin financing for new projects, buyers are increasingly wary of committing to traditional long-term contracts because of the uncertainty around the resilience of gas demand beyond the mid-2030s. The trend is particularly acute in Europe with EU policy aiming to minimise gas consumption in the medium term. Utilities typically won’t want to commit to contracts longer than 15 years.

In spot markets, LNG sellers will always choose a higher bidder. In the end, all it took to drive current gas prices sky-high was economies recovering faster than expected from the pandemic against a background of falling natural gas extraction in Europe, Gazprom’s reluctance to increase pipeline gas supplies, and flexible LNG contracts that allowed LNG suppliers to reroute flows to Asia where the buyers simply paid more.

Recently announced LNG price cap in the European market also benefit Asian end-users as some of the suppliers might want to redirect their cargoes to Asia instead. Consequently, this will in turn raise the LNG price in Europe again.

Increased LNG Supplies in Direct Conflict with Climate Change Objectives

There is yet another principal issue with increased LNG imports. The making and shipping of liquid natural gas is extremely energy intensive. To prepare natural gas for shipping, it needs to be cooled to approximately minus160 degrees Celsius. As the gas liquefies, it shrinks, and becomes six hundred times smaller, making it much easier to transport. Special tankers with insulation and auto-refrigeration keep the natural gas in liquid form as it is transported over massive bodies of water. Once the LNG reaches its destination it is stored or re-gasified back to its gaseous state. The regasification process involves passing the LNG through a series of vaporizers that reheat the fuel.

While the emissions from burning the gas are the same whether it is piped or in liquid form, the extra energy involved in making and transporting the liquid is significant. Piped gas from Norway, produces approximately 7kg of CO2 per boe (barrel of oil equivalent), but for LNG imports into Europe, the same gas volume produces 70 kg of CO2 per boe, making carbon emission ten times higher for LNG versus the piped gas.

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the average yearly CO2 emission from the production and transportation of LNG into Europe was estimated at around 65 million tons. By the end of this year, if Russia fully turns off the gas transit, and all that additional gas needs to come from LNG sources, Europe will see an additional 35 million tonnes of CO2 emissions (yearly) compared to 2021 and 2022 values.

Interestingly, under a new law agreed between member states and the EU Parliament just a year ago, the bloc agreed to cut carbon emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared with 1990 levels. It is easy to notice that this emission target just became non-achievable and non-binding in the face of increasing LNG supplies.

Because of the high carbon emissions occurring during the liquefaction, the climate benefits of using natural gas are offset. It will be hard for European policymakers to meet ambitious climate agendas and net-zero targets when using LNG in such amounts. Gas produced domestically would emit significantly lower volumes of CO2.

The strategy of high LNG supplies particularly seems to be illogical since initiatives reducing carbon emissions imposed on EU members created a situation where the countries abandoned their original fossil fuel production. The same fossil fuel production would come in extremely handy during the current energy crisis which Europe is experiencing now.

“Qatargate” Shows No Easy Alternatives On LNG Market

With Europe desperate to ditch Russian gas, the European Parliament corruption crisis shows there’s no easy alternative. The alleged Qatar corruption scandal engulfing the European Parliament could not have come at a more awkward time for gas-poor EU countries — and for Germany in particular.

As a major exporter of LNG, Qatar (with 19 bcm delivered to Europe in 2022) is also vital to Europe’s plans for coping with the energy crisis. Overall imports of Qatari LNG represented just under 20 % percent of the EU’s gas imports last year. But the importance of Qatar to Europe’s energy security is set to grow due to a mega-expansion of its LNG production capacity, with two major projects scheduled for completion in 2026 and 2027.

Berlin is among the EU capitals most desperate to secure alternative supplies of gas, having been dependent on Russia for no less than 55 percent of its supply before the war in Ukraine. Unable to secure LNG imports on the spot market, Germany signed a 15-year gas contract with state-owned QatarEnergy and the U.S. firm ConocoPhillips, guaranteeing stable LNG supplies starting from 2026. That is the year when the first phase of Qatar’s capacity expansion — a Persian Gulf development known as North Field East — comes on-stream.

Several European countries — such as Italy — have become more interested in Qatari LNG, but most of them have discussed spot market deals” that would supply gas immediately. Germany is the only EU country that has signed a significant long-term energy agreement with Qatar.

However, Germany is not the only EU country with deep energy ties to Qatar. French energy giant TotalEnergies holds significant stakes in both the North Field East LNG development, which it describes as the world’s biggest LNG project, and its sister project, North Field South. Italy’s Eni also holds a stake in North Field East.

Although bribery is a criminal offense, it would appear that this doesn’t stop European countries from striking gas deals with the government accused of such criminal actions. That deal, while good for energy security, risks becoming an ethical nightmare for countries like Germany now tied to Qatar by a 15-years long contract.

Conclusions for Poland and Eastern Europe

- Europe’s historical reliance on gas — and particularly on Russia as the main importer of gas — has created a serious supply problem in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The shortage of gas supplies extends way beyond this winter as the EU initiative for falsely understood prevention of high carbon emission pushed the continent into a precarious and significantly weaker energy position.

- The West had mistakenly ignored the warnings of Poland and the Baltic states about Russia weaponizing its energy resources. Poland and the Baltic states for years have been subjected to Russian energy blackmails, gas supply cut-offs, and unexpected changes in gas supply levels. The Eastern countries on several occasions criticised the European energy strategy of relying on Russia as a stable and reliant gas supplier. Western EU members (e.g. Germany) continuously ignored warnings of possible Russian gas blackmail with the construction of the Nord Stream 2 accomplished only months before Russian aggression in Ukraine. Only Russian military aggression in Ukraine prevented Nord Stream 2 from being certified, otherwise, the dependency on Russian supplies would have only deepened. The current crisis is a direct result of ignoring these warnings and Europe is paying a high price for its dependency on Russian gas.

- Poland and Baltic states abandoned gas supplies from Russia at the most optimal time. Because of that, although suffering from the high gas prices Poland is in a relatively safe energy position. Recently opened Baltic Pipe operates at its full capacity of 10 bcm. Domestic gas production may reach 5.5 bcm this year. Poland has also secured the import of liquefied natural gas via the Lithuanian LNG terminal in Klaipeda with a volume of 2 bcm. Gas interconnector with Slovakia also provides bigger flexibility in diversification of deliveries. The LNG terminal in Swinoujscie is planned to be expanded to 8.3 bcm this year. The country might also build two floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) due to the interest of the Czech Republic and Slovakia in buying more LNG via Poland. The project already received EU funding. Qatar continues to be the primary LNG importer with the USA, Norway, Nigeria, and Trinidad and Tobago following.

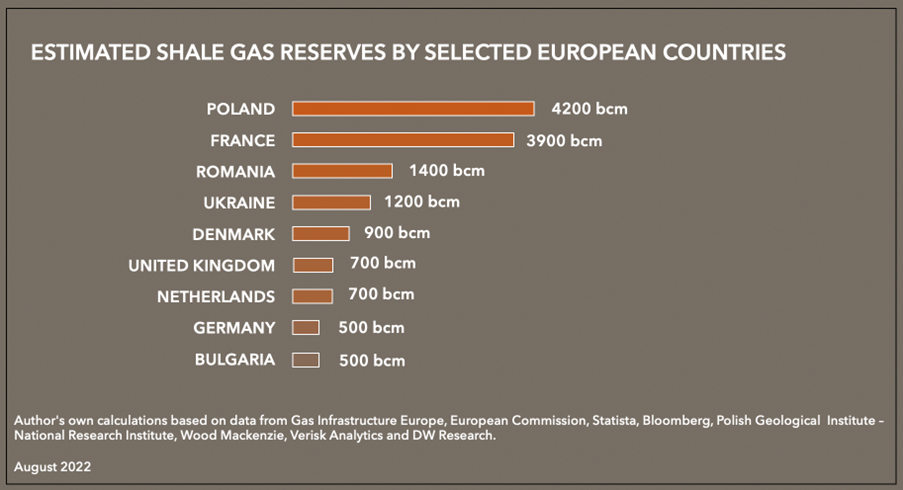

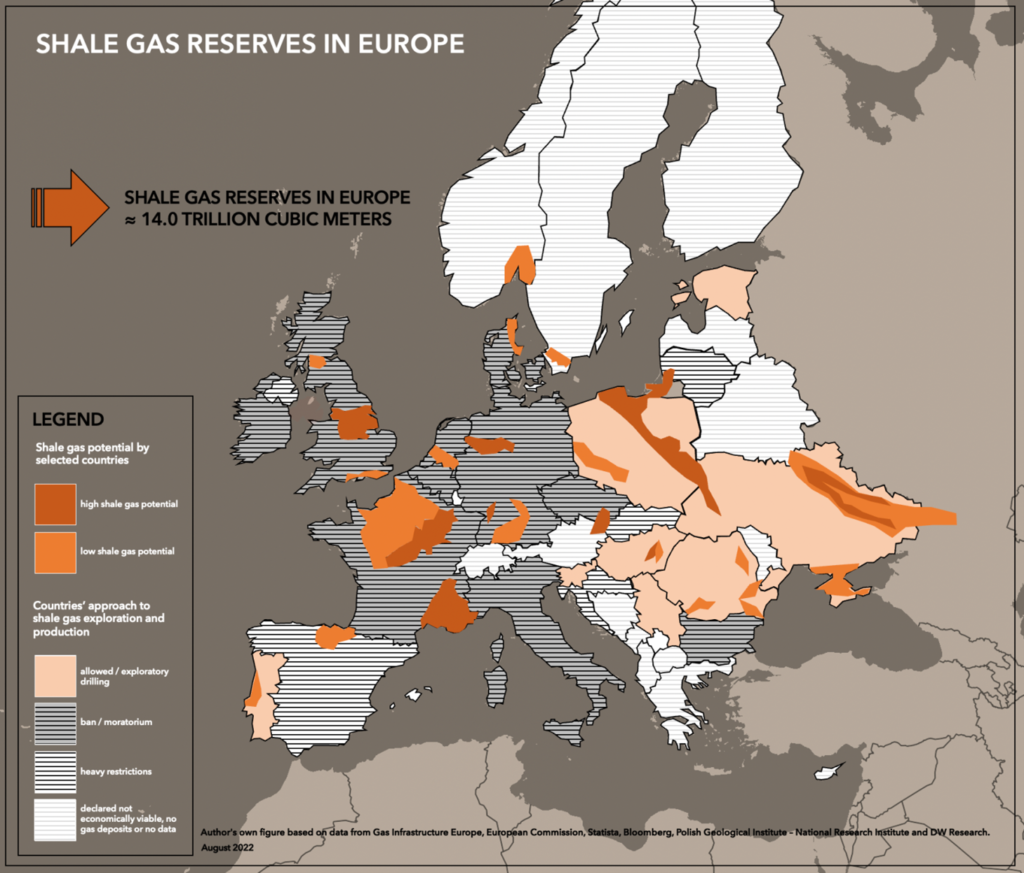

- The country should however continue the diversification of gas sources and shift its attention to domestic gas production. Only when Poland develops their own viable an secure energy source, the country will always be subjected to potential external energy security threats. Although currently there is no shale gas production in Europe, this unconventional gas source should be brought back to the table to alleviate the European energy crisis. Exploration and production of the European shale gas reserves have long been shelved due to mounting reactions from environmentalists. With the largest unconventional gas reserves in Europe estimated at 4.2 tcm (trillion cubic meters,) Poland should lead the talks within the EU to create new relevant EU legislation for shale gas exploration and production (figure 3). Even with a fraction of the mentioned 4.2 tcm produced, it would still elevate the country to the major league of gas producers in the region and allow to improve European energy security. Current high gas prices and the energy crisis create a suitable environment for it. Especially when European countries that banned shale gas exploration and production in the past due to environmental consequences (figure 3) are now buying resources extracted by the US using the same method.

FIGURE 3. Shale gas reserves in Europe and countries legislation approach to shale gas exploration and production. Figure depicts data as of August 2022.

TABLE 3. Estimated shale gas reserves by selected European countries. Presented calculations as of August 2022.

Author: Piotr Przybyło , Resident Fellow at Casimir Pulaski Foundation