Vladimir_Putin_and_Kim_Jong-un_(2024-06-19)_03

Autor foto: Presidential Executive Office of Russia

Vladimir_Putin_and_Kim_Jong-un_(2024-06-19)_03

Autor foto: Presidential Executive Office of Russia

The Axis of Upheaval: Russia, PRC, DPRK, and Iran

Autor: Reuben F. Johnson

Opublikowano: 19 grudnia, 2025

An Evolving Axis

The “Axis of Upheaval” is the latest moniker that is used as shorthand to denote the increasing cooperation and alignment of interests between the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia, Iran, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), or North Korea. While the four nations have shared interests of a transactional nature there are few longer-term or strategic goals that the nations have in common. An example would be that Russia provides energy exports to the PRC while Beijing in turn provides numerous manufactured goods and industrial inputs that are otherwise denied to Moscow by sanctions.

While there are tactical reasons why this arrangement suits Russia for the moment, a continuation of this dynamic will only serve to exacerbate the disparities between the two nations. In the 1990s the PRC, which was starving for the defence-industrial know-how and the insights into how to design and build weapon systems that Moscow could offer, was most decidedly the junior partner of the two. However, in the present day the tables are most definitely turned in the other direction. Continuing their present arrangement will only result in Russia becoming increasingly eclipsed by the PRC’s lengthening shadow.

As a recent assessment of the widening disparity between the two nations points out, “China’s GDP is five and a half times larger than Russia’s. Their cooperation is largely confined to Russian energy exports and Chinese exports of goods and equipment, which are essential for Russia due to western sanctions. Yet Beijing avoids broadening its economic relationship with Russia to include investment and technology transfer, reinforcing one-sided dependence.”[1]

But rather than multi-faceted partnerships that are based on a set of shared values and a program of joint ventures and international cooperation, the “alliances” between these four nations come down to little more than them being united in their opposition to the US-led, rules-based global order. That anti-Washington, anti-NATO sentiment and the desire to take any possible actions to disrupt the current status quo has always been present to an extent, but it has only accelerated since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Prompted by Russia’s failed attempt to subjugate Kyiv and deepening internal problems, the members of this axis have nonetheless eschewed the establishment of a formal military alliance. Instead, they are engaged in an episodic, escalating and deepening military, economic, and technological cooperation. The sole function of this arrangement has no positive objectives or set of proposed accomplishments, but is designed to instead challenge Western international political hegemony.

This explains why these four nations—which sometimes also include the support of the Latin American nations of Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba—do not work towards major cooperative international initiatives. They only provide mutual support to address immediate situational requirements, like Iran providing drones for Russia or North Korea providing soldiers, workers, and artillery shells for Moscow’s war against Ukraine. To the extent that they share strategies they are more like four co-dependents supporting each other’s efforts at disruption, with the overall concept that a combined set of challenges to US security strategies will result in an alternative world order.

This primary group of four nations has been given any number of titles: the “Axis of Revisionist Powers” is one. The “Axis of Autocracies” is another. “Quartet of Chaos,” breaks the traditional mould but is perhaps even more accurate. Whatever label is used to describe them collectively, it is not by accident that the grouping of nations is referred to as an “axis”.

That labelling is purposeful. The word conjures up images and memories of the original Axis powers of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan. The intent is to send the message that any similarly named group of nations possesses the same qualities of evil. It is meant to place them in the category of being as dangerous, duplicitous and degenerate as their WWII forebearers.

In the parlance of the post-Cold War era, a group of nations referred to as an “axis” also places them as today’s latest edition from a lineage of villainy, thereby transforming the challenge they present to free nations into an echo of the original Axis powers. As the American historian Walter Russell Mead wrote in the Wall Street Journal this past summer, “the [current] world crisis is bigger than Asia. China, aligned with Russia, North Korea, and Iran, has formed an axis of revisionist powers aimed at challenging the existing world system on every continent, at sea, in space, and in the cyberworld.”[2]

As another recent analysis of this arrangement points out, “the four countries in this ‘axis’ (…) have little formal coordination. But the phrase captured something about mood and moment: the sense that the world is tilting toward multipolar rivalry and systemic friction.” But, as the same assessment continues, “Calling a coalition an ‘axis’ is never a neutral act—it is a political label. It can transform separate grievances into one unified struggle, or it can reduce a complex relationship to an ‘us versus them’ or ‘good versus evil’ frame.[3]

The Nature and Objectives of the Axis

The members, as mentioned above, are: China (PRC), Russia, Iran, North Korea. The countries’ names are sometimes bundled in the acronyms CRINK or CRINGE, the latter being employed when extremist groups and other non-state actors are lumped in. The collective threat that they represent is having ripple effects across the world and into regions that are nowhere near the European theatre – which is where the war in Ukraine that has solidified their alliance was begun and continues to cause no end of death and destruction.

The actions of the Axis have now prompted cooperation between NATO and other democratic-values nations in the Indo-Pacific region. In 2024 and for the first time, senior officials from Australia, New Zealand, the ROK, and Japan began participating in the regular meetings with NATO defence ministers. “It’s extremely positive that these four countries are participating more and more with NATO allies,” the alliance Secretary-General Mark Rutte told reporters at the time, “because of the simple fact that security threats in the Indo-Pacific, of course, have a link to what is happening here, and you cannot simply divide the world.”[4]

But what motivates the members of the Axis is not a set of positive objectives or the goal of building a new, better, more just world order—quite the contrary. The Axis members, half of whom (not surprisingly) are also part of the BRICS grouping of nations, have as their solitary, overarching goal promoting opposition to what they regard as US hegemony. Their “planning”, as it were, when it comes to initiatives or proposed cooperation is a set of disruptive activities that are focused on overturning the existing international system of political, military, and economic relations between nations.

But in the set of agreements, pacts, and other communiques that the different members of the bloc have made with one another there are almost no examples of mutual, bilateral or multilateral commitments. There is no analogue to the Article 5 of the NATO treaty that would require the nations to come to the aid of any single one of the Axis members in the event of an attack. The most visible example is that when Iran came under attack by the US and Israel for almost two weeks in June of this year, none of the other Axis partners credibly threatened to, or actively did, intervene on Iran’s side.

This trend of “promising to be friends but absent any benefits” began in 2021 when the PRC and Iran signed a 25-year strategic partnership agreement. In 2022, Beijing and Moscow famously solemnly declared a “no-limits” partnership.

But as discussed above, some number of unspoken limits apparently do exist. The PRC-Russia agreement amounts to little more than a monetised countertrade arrangement of Russian energy in exchange for PRC defence industrial and economic aid. The absence of a commitment to any broader set of cooperative engagements is conspicuous to say the least.

One of the terms instead used to describe this alignment of the four nations is “an economic assistance arena.” And like most economic assistance arrangements it is not a collective of equals. There are always going to be junior and senior partners, and naturally the senior partners will more often dictate terms to the junior ones. It also creates some rather pronounced dependencies in which the junior partner would suffer immediate shocks to their economic or military systems if the main areas of cooperation suddenly came to a halt

A more cynical interpretation might be to call their commitments, to the extent that they even exist, as “marriages of convenience.” The question is, therefore, what happens to these arrangements when they are no longer as convenient as they once were.

As compensation for millions of rounds or artillery shells and thousands of soldiers sent by the DPRK to fight on the front lines in Ukraine or carry out de-mining operations, Moscow has imported thousands of workers provided by Pyongyang. Those workers, some of whom work in Russian munitions plants re-manufacturing the many defective artillery rounds sent by the DPRK, or are assigned to construction projects, earn hard currency for Kim Jong-un’s regime.

It is almost the only capability he has to make sums of this magnitude given his nation’s international isolation. At the same time the PRC remains North Korea’s most important economic partner and conducts 98 per cent of Pyongyang’s foreign trade revenue.[5]

Meanwhile, the PRC also purchases 90 per cent of Iran’s oil exports and roughly half of Russia’s as well.[6] This provides those states, which are largely cut off from the international banking system and the rest of the world’s economy in general, a lifeline of state revenue that they cannot afford to be severed.

A majority of this trade activity is carried out in transactions made in Chinese yuan and Russian rubles. This again is a blow against US economic hegemony, as it amounts to a de-dollarisation of international trade. A reduced international reliance on the dollar as the default foreign trade and reserve currency of choice, is still somewhere off in the future, if it ever happens to come to pass at all. But the Axis sees any steps towards limiting the US influence in global markets as not just one of their prime objectives but that same non-dollar trading activity also creates the motivation to build mechanisms for the grouping’s members to circumvent Western sanctions.

Then there is the military dimension. In January 2025, Russia and Iran signed a 20-year defence pact pledging closer military relations. However, the document contained no mention of any mutual defence commitment. Half a year later in June, Iran and the DPRK agreed to a mutual defense pact. After years of providing essential military support for Russia in its war against Ukraine, Tehran likely “expected something more than sternly-written letters from Moscow” after joint attacks by the US and Israel, said a former NATO intelligence officer who commented on the situation. The support from Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Russia was little more than symbolic.

The PRC and DPRK also issued statements condemning the Israeli attacks, but no steps were taken to materially support Iran or even demand a ceasefire. The rhetorical record of all the states that are supposed to be interested in supporting Iran whenever and wherever possible says that they are committed to restraining the use of military power by the US. Their official statements condemn what they say is a dangerous and destabilising tendency on the part of Washington to normalise the use of force in international relations. But none of them were willing to take any action other than denunciations on paper.

This is perhaps the clearest example of the limitations of this Axis. Once the prospect of becoming involved in a conflict with the US and its allies to a level that would potentially require significant kinetic responses, or extending economic commitments that are disproportionate to the benefits they receive in return, the support from the other bloc members falls off sharply.

On 12 December 2025, the European Union decided to keep the €210 billion in Russian central bank assets located in EU financial institutions—largely in Belgium—frozen indefinitely. The system that had been in place until now required Brussels to renew the freezing of the assets every six months. The question has therefore been raised as to what happens if those assets are eventually turned over to Ukraine as reparations. In that case, Russia’s capability to financially sustain the war could very well collapse.

In that instance what would be Beijing’s next move?

In July, the Hong Kong-based, English Language South China Morning Post reported that PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi had told the EU’s top foreign affairs official, Estonia’s Kaja Kallas, that Beijing cannot afford for Russia to lose the war in Ukraine. If that were to be the outcome, the US and its partners would immediately re-orient their military assets to defending the Republic of China (ROC) on the island of Taiwan. Wang’s comments telegraph that Russia continuing the war in Ukraine serves the PRC’s strategic interests and the war ending in a total Russian defeat would be one for Beijing as well.[7]

The question is how far and for how long these interests could continue to be the central factor in the PRC’s continuing to provide economic support for Moscow. Beijing is happy to keep supplying dual-use industrial inputs for Russia’s defence industry and to assist Moscow in circumventing western sanctions by purchasing huge quantities of Russian oil. But this is for the simple reason that the PRC receives some tangible benefits in return. There is no element of altruism in this decision.

Beijing has no security of supply for oil and other energy assets. The ability to purchase them at prices that are so favourable that they would have been unthinkable before the Ukraine invasion are a suitable—and lopsided in favour of the PRC—arrangement. But what happens when the situation becomes one in which the Chinese would have to underwrite the entire Russian war effort and receive nothing in return other than the belief that this keeps the collective West preoccupied. Should it even come to pass, it is not likely to be an arrangement that the PRC would wish to sustain for any length of time.

What Kind of Cooperation and What Prompted It

It is simple to understand what has pulled together these nations bent on upheaval of the world order into some manner of a cooperative arrangement. It was the Ukraine war—plain and simple. This should silence those who were saying for years that there was no linkage between Putin trying to destabilise and take over Ukraine on one hand and what takes place in Asia on the other. But despite insurmountable evidence to the contrary there are those who are still touting the same line that they had before the invasion.

The US and its NATO allies and other partner nations lined up on the side of supporting Ukraine was an irresistible chance for the Axis of upheaval to try and damage and disrupt the solidarity of the democratic western-minded nations. The corollary became that Russia must be supported anywhere, and in any manner possible. Putin losing his war was not only something that the PRC could not afford to happen. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was also a cause that all of the Axis partners were going to benefit from militarily.

There were already relationships in both military and economic spheres on differing levels between the four nations before the Ukraine war. But when Putin’s brash predictions of taking the capital, Kyiv, in a matter of days failed to materialise the dynamic was altered considerably. Cooperation between the four that had existed in the past was now transformed into a far more expanded set of activities, evolving now to a dependence by Russia on the other Axis partners, and for which there are notable examples.[8]

Iran became the key supplier of the Shahed drones,re-named Geran in their Russian-produced version. Tehran also handed over to Moscow the design documentation needed to licence-manufacture them locally. Since that cooperation began the Shahed and other derivative drones have become the most-manufactured foreign defence item or weapons system in Russian history.

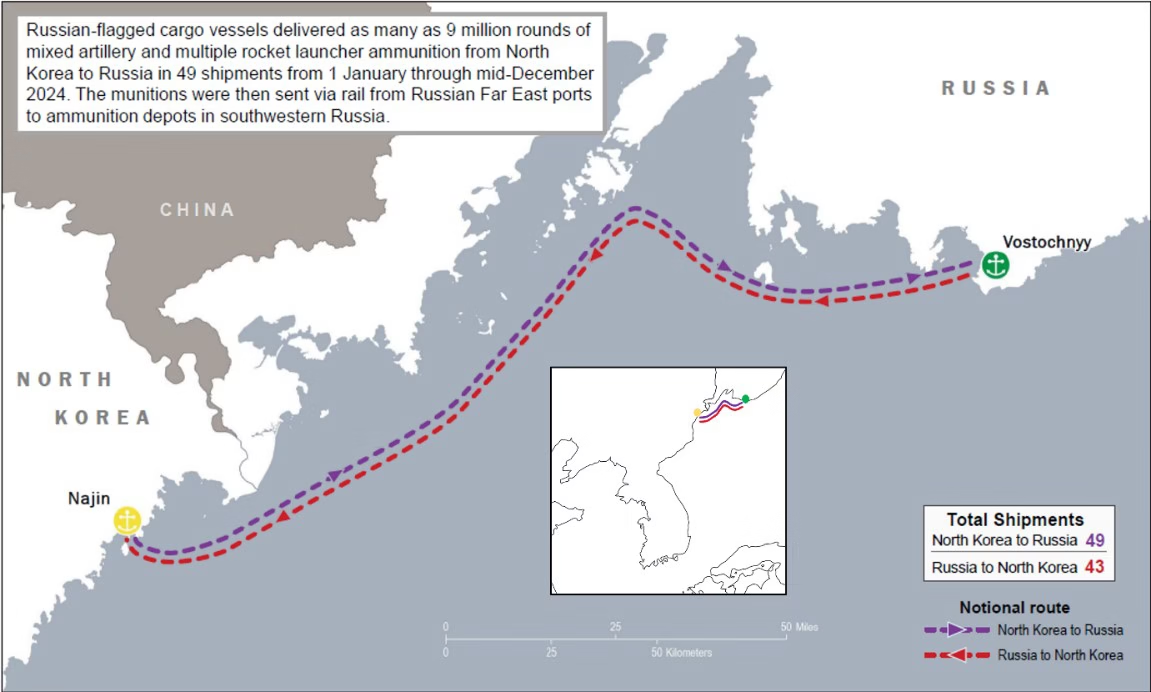

In another set of transactions, the DPRK began supplying ammunition in rapidly escalating quantities to Russia. This was critical at the beginning of the war when Putin’s own defence enterprises could not keep pace with the consumption rates on the front line. This defence cooperation also soon became a dependency on the part of Moscow.

Then, in 2023, military-technical relations with the DPRK were concurrently elevated to a new level when in September the North Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-un visited Russian President Putin. The meeting of the two and the follow-on actions that took place were all clear and very public signs of the augmented cooperation between the two. During the trip, Kim and Putin visited the production sites for Sukhoi Su-35 and the stealthy-design Su-57 fighter aircraft at the Komsomolsk-na-Amure plant in the Russian Far East province of Khabarovsk. They also visited the Russian Pacific Fleet headquarters at Vladivostok, as well as the Vostochny Cosmodrome, which is a Russian spaceport. This also included tours of some of the missile design and production facilities that support the Cosmodrome operations.

Shortly after this visit, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington reported a marked uptick in activity at the DPRK Tumangang rail facility that borders Russia. The conclusion was that the two leaders had come to terms on several major agreements with the DPRK increasing its supply of items like artillery shells and other military-related items to Russia. This would explain the dramatic increase in rail traffic.[9]

In return, the DPRK has been promised several highly sought-after items from Russia that had been denied to them for years. In exchange for providing the Kremlin with manpower and a steady flow of munitions, North Korea is now receiving Russian assistance that is enabling the country to modernise its military and to do so at a pace that is unprecedented in the nation’s history.

Some of the reported upgrades to DPRK military capabilities that are first-order benefits to their cooperation with the Kremlin include Russian funding and technical support for military programs Pyongyang has had in development for some time, such as IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles), SLBMs (submarine-launched ballistic missiles), ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles), etc. Another high priority is the provision of air defence equipment and anti-aircraft missiles, advanced electronic warfare systems, and technical and industrial assistance for the further development of North Korea’s ballistic missiles. Much of this transfer of weaponry and defence industrial capability has been transported not just by rail but also by sea-going cargo vessel shipments, most of which have been tracked and recorded.[10]

By providing Russia with ballistic missiles for attacks on Ukraine, North Korea has also gained unprecedented experience in modern warfare. This is making it possible for the Korean People’s Army to increase the accuracy of their existing missile guidance systems. Also with Moscow’s assistance, the DPRK is developing Shahed-like attack drones similar to those used by Russia to strike Ukrainian cities, according to the Ukrainian Military Intelligence Service (GUR) chief Kyrylo Budanov.[11]

This process of military technology transferring from Iran to Russia and now being passed onto the DPRK will become the pattern for the near future—as will pathways that operate in the reverse involving other weapon systems. One can count on this now becoming a permanent state of proliferation from one hand to another and working in both directions.

Routes taken by Russian-flagged vessels delivering arms and related materiel between North Korea and Russia from 1 January to mid-December 2024. Source: Unlawful Military Cooperation including Arms Transfers between North Korea and Russia, Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team, 29 May 2025.

Weapon systems and the means to produce them or modernise them acquired by one nation will be passed on to another, which will then pass it to the other Axis nations. Whatever constraints or export restrictions might have been in place for decades that one nation might have adhered to avoid being sanctioned appear to no longer be in force.

The DPRK has long sought advanced Russian military systems like more sophisticated fighter jets, advanced air defence batteries and the missiles to go with them, electronic warfare (EW) systems, satellite design technology, and critical assistance for its nuclear and missile programs. The latter is especially significant in that it is being utilized by Pyongyang’s Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM) and Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) programs.

Remnants of Hwasong-11A short-range ballistic missile obtained in Ukraine. Source: Source: Unlawful Military Cooperation including Arms Transfers between North Korea and Russia, Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team, 29 May 2025.

Pyongyang receives all of this in exchange for artillery and missiles sent to Ukraine. These capabilities plus food, oil, and high-technology industrial blueprints/expertise to modernise its conventional forces, drones, and space capabilities. The DPRK’s goal in acquiring these technologies is to enhance its overall military power so that it possesses current-day conventional military forces. This then creates an armed forces that are equipped with destructive conventional systems—military power other than that that comes from owning nuclear weapons.

Russia supplying the Shaheds to the DPRK is an excellent, although not the most high-technology, example. This weapon will give the DPRK the ability to hit targets anywhere in South Korea and potentially in large numbers. They can overwhelm ROK air defences and in so doing deplete Seoul’s supply of air defence missiles. Large-scale attacks with this class of weapon will also pave the way for attacks by other munitions.

The KN-23s Short Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBM) are another case where both sides benefit from cooperation. The first batches provided by the DPRK to Russia were described as “woefully inadequate.” According to a report from Ukrainian state prosecutors around half of these missiles, which are also known as the Hwasong-11, not only deviated from their trajectory after launch—in some cases by more than several kilometers—but some of them even exploded in midair.[12]

Since then, that missile’s design has been markedly improved thanks to Russian technical support. Budanov told one of the major US defence publications that thanks to the enhancements to the design the KN-23s are now striking with deadly accuracy. This has not only given Russia a desperately-needed source of SRBMs but has greatly improved the missiles that the DPRK now has in its own arsenal.

Conclusions

There are several significant overall implications that are by-products of the cooperation of all four of the Axis of Upheaval nations. What can be said is that almost all of them benefit from this arrangement. Most all of them emerge from their shared partnerships and defence cooperation arrangements with improved capabilities. They all will end up with larger defence industrial establishments and—perhaps with the sole exception of Russia—more modernised defence sectors.

The PRC are benefitting in numerous ways from the relationships of the Axis and more so than any of the others. Xi Jinping is gaining access to a wide range of Russian defence technology that Beijing had been seeking access to for many years. These represent some of the last areas in defence tech in which Russia has had a real advantage over the PRC, but which Moscow had been holding back on. The PRC are also able to receive considerable energy exports from Russia at prices so unfavourable to Moscow that they would have been unthinkable for the Chinese to have even proposed them in the years before the war began.

The strategic situation for the PRC is also significantly improving. By the time the Ukraine war is over, it will have continued a rapid and wide-spectrum military build-up. The western powers that Beijing is anxious to see maintaining their fixation on the war against Russia are likely to be shocked at the degree to which they will end up being behind the PRC in military industrial and technological capabilities. The country is also likely to see itself more prepared than ever to contemplate a takeover of the ROC (Taiwan).

The nations aligned with the US in the region will have to try and strengthen their alliances to counterbalance the PRC. But without a significant uptick in all their defence expenditures they will all struggle to do so. If there is a potential sticking point for the PRC it is that the nation continues to chafe under an increasingly repressive police state dictatorship. The degree to which the Chinese Communist Party seeks to control the thoughts, the actions, the lives of its citizens is one that is producing progressively more unrest rather than less.

The question remains if this current order under Xi Jinping can maintain power indefinitely. While the population is bombarded with the usual Communist propaganda that says “only good things are happening in China” all day long, there are growing economic problems and those satisfied with the standard of living are a decreasing percentage of the population.

There is also the fact that Xi has been trying to stamp out corruption in the PLA for more than a dozen years and yet has failed to do so – witnessed by his October removal of some nine generals and admirals, including two members of the Central Military Commission. It is the most serious purge of senior PLA officers in half a century, and it begs the question of whether the military are as politically reliable as a PRC Communist Party General Secretary needs it to be.

But Xi having changed the constitution so that he can remain president for life is not as many think a sign of a strong political leader who need not fear a challenge to his power. The reality is that him having rigged the system so that he can have the third term—and potentially even a fourth—is a sign of weakness. If he was a real strongman, he could retire from any official positions and then rule from the background as Deng Xiaoping once did. He needs for the war to continue and for the Axis to stay solidly united because it is his best chance to stay in power.

Possibly the nation that benefits the most from this grouping of nations is the DPRK. Kim Jong-un is enjoying an immense financial windfall from the munitions, soldiers, workers, and other military assistance that he is paid for providing to Russia. In return his own armed forces and his military enterprises are continuing to benefit from a steady stream of Russian defence industrial know-how. It will be the greatest transfer of weapons-making competencies from one country to another since the German military competencies from the Third Reich were acquired by the Soviet Union in 1945.

The improvements that are already being made to the DPRK’s military capability will extend well beyond Russians providing Shahed drones to Pyongyang or showing them how to improve the performance of their KN-23 missiles. Ukraine’s military intelligence services will not detail all the improvements that Russia has made to DPRK weaponry or what other capabilities are being transferred to the Kim’s military.

But the Military Intelligence chief Budanov did say that the degree to which the DPRK’s military is being modernised will extend the dangers presented by Pyongyang well beyond the immediate zone or regions in the ROK adjacent to the DMZ. Russia’s aid to North Korea, as he sees it, will alter the balance of power on the peninsula.[13]

Accordingly, if there is a nation that is jeopardised as much by the war in Ukraine due to its neighbours being strengthened by its defence cooperation with Russia, it is the ROK. Seoul will find itself facing more threats and on a greater scale than even that being brought to bear against the ROC by Beijing.

Iran, like the DPRK but to a lesser degree, has benefitted from the military cooperation that the Ukraine war has brought to them and the defence industrial expertise that Moscow has shared with it. Russia’s need for weapons, particularly drones like the Shahed and ballistic missiles, is what have led the way in this significant uptick in military cooperation for Iran.

In return Iran has enjoyed several benefits. One of them, and perhaps the most important, is a live testing ground in the form of the Ukraine conflict itself. Using the battlefield as the world’s greatest laboratory has allowed Iran to assess the effectiveness of its own weapons and then refine detailed designs of its drone and missile capabilities. More importantly it will permit Iran to improve the survivability of their weapons against the more advanced Western air defense systems being operated by Ukraine.

Russia has also provided Iran with its first access in decades to advanced weapons systems and the technology behind them. Platforms such as Su-35 fighter jets, Yakovlev Yak-130 trainer aircraft, and the Almaz-Antei S-400 air defence systems are just a few examples. At the same time, Russia purchasing so many of Iran’s weapon systems and using them effectively against Ukrainian cities and infrastructure are like an “arms industry seal of approval”. This is a priceless advertising boost to Iran’s own arms export sales. The Islamic Republic is and will continue to be able to sell increasing numbers of its own weaponry to more nations.

There are also political and diplomatic benefits for Iran. The war in Ukraine has forced Russia to rely on Iran, which has elevated Tehran’s strategic value, as well as providing it with political cover and diplomatic support on the international stage.

Both Russia and Iran share a common goal of tearing down the US and Western influences worldwide. In addition to being part of the “grand plan” that would establish a multipolar world in which the US no longer retains a dominant position, the Ukraine conflict diverts Western attention and resources away from trying to dismantle Iran’s nuclear program. It also lessens their ability to stymie Iran’s regional activities in the Middle East.

In the end if there is a nation that loses more than it gains out of being part of the Axis of Upheaval and opposing allied efforts to support Ukraine it is Russia. The effects of the war on the country can be described in the long term as being no less than catastrophic.

When the conflict began there were some 2,000 defence industrial enterprises in all of Russia. Today there are more than 6,000, a massive expansion of this sector in a period of less than four years. This would seem like an archipelago of factories that could produce a military machine of overwhelming size. But the truth is that Russian losses in equipment are anywhere from 2:1 to as unbalanced as 5:1 when compared with Ukraine losses, which requires almost constant replacement of military hardware.

But that expansion and the orders of magnitude increase in Moscow’s military spending are taking their toll in more ways than one. Russia’s economy hangs by a thread with record-high interest rates, most economic indicators falling and few prospects for its increasingly obsolete industrial sector to ever modernise. In fact the reverse is occurring. Economic specialists now openly discuss how Russia is instead “de-modernising”.

Russia was once known as a nation that produced highly advanced weapon systems with fluency in a plethora of scientific disciplines. This technological capability has been hollowed out by the country instead concentrating spending on simple, lower technology items like artillery shells. Its production plants often cannot produce properly functioning weapons without the importation of industrial inputs like foreign electronic components.

Then there are the population-related disasters. Dislocations, economic collapse in the 1990s and other causes already had Russia in the throes of a demographic decline. The effects of the war have turned this into a full-blown catastrophe. Massive casualties, severe sanctions, frozen assets, labour shortages, and brain drain of at least a million educated emigrants, mostly young adults, have all combined to create a pronounced labour shortage. Russia now openly talks about having to import workers and technical specialists. These factors, along with already low birth rates, are severely exacerbating pre-existing trends.

So, Russia, which the other three members of the Axis benefit from what they can gain from it, is the long-term biggest loser in this war. The increasing weakness of the country may in the future lead to it being encroached upon by some of its neighbours, with the PRC being at the top of the list.

It is no small wonder that increasing numbers of Chinese speak about Vladivostok once having been a city that “belonged to China” and that they refer to it by its old name of Haishenwei (海參崴). Some Chinese go so far as to say that this city “used to be ours and some day we will take it back.”

Lastly, Russia will be the worst to suffer from what is predicted to be a widespread phenomenon of nuclear proliferation in the wake of the Ukraine war. Estimates vary, but it is projected that as many as 40 nations could end up having a military-grade nuclear capacity due to their fear of increasing aggressive dictatorships and growing instability. Russia will end up being within striking distance of many of them.

The members of the Axis of Upheaval speak as if they are bringing some new age of enlightened mutli-polar power to the world community. They boast of creating a new dynamic that we can all look forward to: a supposedly more stable world in which no one superpower can dictate to smaller nations. But it is the exact opposite that will likely be the final result of these four nations having banded together to support the one member, Russia, in its war. Russia, for its part, is just as likely to end up in the worst condition than any of the others. Ironically, Russia, which started this war, probably will have to be severely punished by the rest of the world community if the globe is not to be plunged into chaos. The question is which nations will stand with one another when that time comes.

Author: Reuben F. Johnson

Director of Asia Research Centre, Korea Fellow, Casimir Pulaski Foundation

Supported by the Korea Foundation

Bibliography:

[1] “Russia in a multipolar world: equal player or junior partner to China?”, New Eurasian Strategies Centre, 5 September 2025.

[2] Walter Russell Mead, “The War of Revision is Coming”, Wall Street Journal, 2 June 2025.

[3] Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay,“ Force Isn’t Only Wy to Confront ‘Axis’”, Brookings, 24 March 2002.

[4] Stuart Lau, “CRINK: It’s the new ‘Axis of Evil’, Politico.eu, 17 October 2024.

[5] Edward Howell, “North Korea and Russia’s dangerous partnership,” Chatham House, 4 December 2024.

[6] Clara Fong, “The China-North Korea Relationship,” Council on Foreign Relations, 21 November 2024.

[7] Finbarr Bermingham, “China tells EU it does not want to see Russia lose its war in Ukraine: sources,” South China Morning Post, 4 July 2025.

[8] Andrew Latham, “From evil to upheaval and beyond: How the ‘axis’ metaphor shaped modern geopolitics”, The Conversation, 8 December 2025.

[9] Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., Victor Cha, and Jennifer Jun, “Dramatic Increase in DPRK-Russia Border Rail Traffic after Kim-Putin Summit,” Beyond Parallel, CSIS, 6 October 2023.

[10] “Unlawful Military Cooperation including Arms Transfers between North Korea and Russia,” Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team, 29 May 2025.

[11] Howard Altman, “Russia Giving North Korea Shahed-136 Attack Drone Production Capability: Budanov,” The War Zone, 9 June 2025.

[12] Thomas Newdick, “Ukraine Situation Report: Half Of North Korean Missiles Used By Russia Failed, Kyiv Says,” The War Zone, 7 May 2024.

[13] Howard Altman, “Russia Giving North Korea Shahed-136 Attack Drone Production Capability: Budanov,” TWZ, 9 June 2025.